This is, by far, the longest project that I have yet done for this blog. It took me a month to work my way through the whole series, and a bit of will to finish it for this writeup.

This is, by far, the longest project that I have yet done for this blog. It took me a month to work my way through the whole series, and a bit of will to finish it for this writeup.

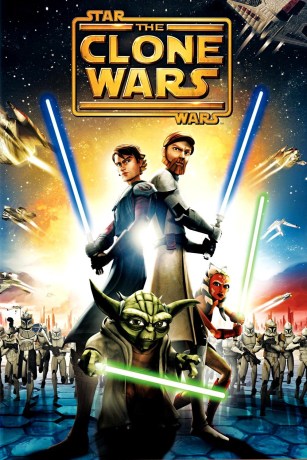

Star Wars: The Clone Wars is a series that, even at 121 episodes and a pilot that was adapted for film, some consider cut short. It follows the adventures of Generals Skywalker and Kenobi during the Clone Wars, as well as introducing a new character: Anakin’s Padawan, Ahsoka Tano.

It starts slowly. Anakin, when we first meet him, is barely more than the same bratty Padawan we first met in Attack of the Clones, one who doesn’t want an apprentice of his own. And Ahsoka, when we first meet her, is very similar: two stubborn personalities dueling with each other.

Yet the series finds its groove. As Anakin teaches Ahsoka, both their heads cool. Ample time is given to explore his relationships with Obi-Wan and Padmé here (though, as in the films, that relationship remains forced and hobbled by a fundamental lack of chemistry between the two. For a quick primer on what real chemistry in the Star Wars universe looks like, look no further than Kanaan and Hera in Star Wars: Rebels). Obi-Wan, too, as a character becomes more developed, and we start to see the sacrifices he made to be a Jedi–specifically the romantic sacrifice Anakin has been utterly unwilling to make.

(Note: Obi-Wan and Duchess Sateen also have better chemistry than Anakin and Padmé.)

This is a show that, at its heart, manages to do a lot with a lot of rough. It’s fundamentally unable to fix massive structural storytelling flaws within the prequels trilogy, of course, but with the material that it does have, it does quite a lot.

Even with the limited ability for Anakin to develop as a character, thanks to this series’ interquel nature, we can see how close he is–has always been–to the Dark Side. Anakin frequently resorts to tactics like Force chokes in interrogations, and, as the series progresses, increasingly blatantly, too. In one character arc, we see the nature of his hamartia, his fundamental flaw: unhealthy white knight tendencies, a desire to protect everyone and everything he possibly can. A vision of his own future was enough to seduce him! Yet ultimately we see foreshadowed, and increasingly heavily, that it is his very conversion to the dark side that brings about the fate that that conversion is intended to forestall.

Anakin’s development is complimented by Ahsoka Tano’s. From a bratty pubescent who probably shouldn’t be allowed to run around on battlefields (but who are we to judge the Jedi’s training methods?), she matures into a capable commander in her own right, as well as someone with a stronger moral center than Anakin’s, a better knowledge of what is right. And in the end, when she elects to walk away from a Jedi Order she feels has betrayed her, she also shows a far greater clarity of judgement than Anakin ever does (except when he’s on the battlefield).

Ahsoka grew up. Canonically, Anakin can’t.

This leads me to what I believe is the overarching fundamental problem with the entire prequel arc: the wrong protagonist. When you watch the original trilogy, it is clear that, while Luke may be the protagonist, the real story is the redemption of Darth Vader. But it’s never, ever told directly. Rather, we see it indirectly, through his actions in A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back as contrasted to those in Return of the Jedi, where the looming, psychopathic Sith Lord shows a caring throughout the film (in his dealings with Luke) that we had not seen from him before.

In other words, while Episodes I-VI may be Anakin’s story, first of his rise, then of his fall, and finally of his redemption, it is best told from the perspective of others associated with him, rather than he himself. In practical terms, this means that the prequel trilogy should really have been Obi-Wan‘s story, the conflicts that we focus on as primary Obi-Wan‘s. That means we should be focusing on him asking himself whether he’s cut out to be Anakin’s teacher, and we should see him attract a nemesis of his own, i.e. Darth Maul. Actually, in The Clone Wars, he does start attracting nemeses, being shown to have developed a history with every major Separatist player, and yes, even with Darth Maul. But he was never given the central role that should have been his.

Likewise, The Clone Wars was Ahsoka’s arc, the arc of her training under Anakin and her ultimate forsaking of the Jedi Order. That was what would thematically bind the whole series together. She needed to be the protagonist: she had the most individual character development, the effect of her absence from Anakin’s side being to hasten his fall to the dark side. Her conflicts, and how she dealt with them, needed to be central to the story. The fact that it wasn’t is something that I don’t think even Filoni could have helped–and that leads into what is the main failure of The Clone Wars as a series:

Everything it does wrong, it can’t help: it’s bound by canon. And the canon here, especially the canon mode of storytelling, is what’s problematic.

Anakin may have the main story arc of Lucas-era Star Wars. But he should never, ever be a protagonist character. Not as Anakin Skywalker, not as Darth Vader. That is what the original trilogy got so right; that is what the prequel trilogy got so fundamentally wrong.

4/5. Dave Filoni makes diamonds out of the coal he’s got. Plus, the Ahsoka of later seasons is amazing.